What Didn't Work (posted 04 Apr 2011)

I just defended my thesis and took my oral comprehensive exam. I passed! I still have to clean up the thesis itself, but in the meantime, here’s a somewhat supplementary blog article. Here, I try to document some of the ideas that didn’t work, or just didn’t end up being useful, and what could be learned from them.

Before you go on: You’ll probably want some sort of background on what, exactly, this whole “thesis” thing is about. So:

Alternately, just read the first part, which should give you a vague idea as to what the actual problem is.

Okay. Still with me? Read on.

Ellipsoid Measurement Space

When I first looked at this problem, I conjectured that the “shape” of the measured conductivity space in spherical coordinates, where phi and theta mirrored real-world orientation and radius corresponded to measured conductivity, would have an ellipsoid shape. That is, I suspected that the equation

x'Kx = 1

would hold, where x is ||1/k|| long and in the measured direction, and K is the conductivity matrix. However, this is clearly not the case.

This is, in part, not the case because the needle isn’t measuring conductivity parallel to the needle, but orthogonal to the needle, and some sort of average of said orthogonal conductivities at that. In retrospect, this is obvious.

I suppose the lesson here is to make sure you fully understand the problem before making wild conjecture.

That said, this is a good method for conceptualizing eigenvalues, given that your matrix is symmetric and positive definite. It’s called “Lame’s Ellipsoid” in certain contexts, and is used in discussing equivalent energy states in certain dynamics problems and sometimes as an alternative to Mohr’s Circle. In fact, Mohr’s Circle itself helps visualize eigenvalues admirably, though in many problems outside material mechanics a shear component doesn’t make sense. I mean, “shear conductivity?” What’s that?

Open-Source FEM Toolchain

As I became somewhat disheartened over a lack of initial success with COMSOL, I began exploring other tools. In particular, I was interested in using open-source finite element tools. A number of tools do exist, but the situation isn’t good, as I outlined in this reddit post, likely written in December 2010:

I know this was posted months ago, but seeing that nobody really said anything: I’ve done some research on open-source finite element analysis and think I might be able to shed some light here.

Before I do, I noticed that you mentioned Abaqus, so I’ll address free-as-in-beer modeling first. All of the commercial codes cost money, but their target audiences are also organizations and not people; As such, with enough searching you may be able to find some cheap or free student editions. One of my professors was shopping around an Abaqus student edition that just limited you in terms of mesh size such that you couldn’t really do problems that required fine meshes in 3-D but could get yourself going if a coarse solution was okay.

In terms of open-source software, here’s my impression: It’s out there, but it’s often unpolished and typically not all-inclusive the same way commercial codes are. In a full FEA stack, you basically have four parts:

- Modeling. This is when you say, “my domains are shaped like this and act like that.”

- Meshing. This is when you split your domains into little tetrahedrons (or whatever other shape makes sense).

- FEA proper. This is when the program actually uses a finite element formulation of your governing equations to find a numerical solution. This is the part that requires iron.

- Visualization/Post-Processing. Once a solution is obtained, it needs to be visualized somehow. This is where pretty pictures and graphs comes in.

In the open-source world, there are tons and tons of programs and codes that can do all of these things, but they tend to be more decoupled and have a higher learning curve. Some of them are better for some things than for others. I haven’t been successful in learning a full stack yet and this list is far from exhaustive, but here are a few things I’ve ran across:

Salome, I believe, aims to be an interface to the full stack. That is, it uses third-party meshers and solvers to do the heavy lifting, and takes care of steps 1 and 4 in a more common-style one-stop interface. Last time I tried to use it I found it pretty incomprehensible but it was also years ago so ymmv.

ELMER is a one-stop solution, I believe. It’s modular in construction, but all the major pieces are there. On the other hand, while its learning curve isn’t terrible and it has decent docs last I checked, I’ve also heard that its solvers aren’t the best. Of course, for simple problems, simple solvers suffice.

GMSH is a stand-alone mesher. Its style is a bit different from some 3-D modelers, but it seemed to work alright if you didn’t need to force the mesh to be really tight in some areas and coarse in others.

MeshPy looks good from meshing, and Andreas makes good software. However, there seems to be disappointingly little in the way of online documentation.

OpenFOAM is, I believe, one of the standard solvers that Salome uses. It’s a relatively common CFD package. I otherwise don’t know much about it.

Dolfyn is another CFD package I heard about while researching a long time ago. I honestly don’t know anything about it.

sfepy should allow for FEA using python. However, the rest of the stack is up to you, and I don’t think it’s been proven “in the wild.”

Paraview is a common visualization tool, and I believe many open source solvers output their results in the “old-style” paraview format.

Mayavi is another option for visualization.

If you’ve learned anything else about free modeling/analysis, I’m definitely interested. Like I said, I’m pretty sure this is just scratching the surface.

At the time of authorship, these tools were much more fresh in my mind than they are now, so I’ll let Past Self speak in my stead.

Parallelism

Last summer, after making the first iteration of my model, I found that simulations took a while to run. At about the same time, I attended the Scipy 2010 conference, and I saw a talk—I believe by David Beasley—about “DIY concurrency.” Despite Beasley’s obvious bias towards python-based solutions, it was a really good talk.

I felt inspired.

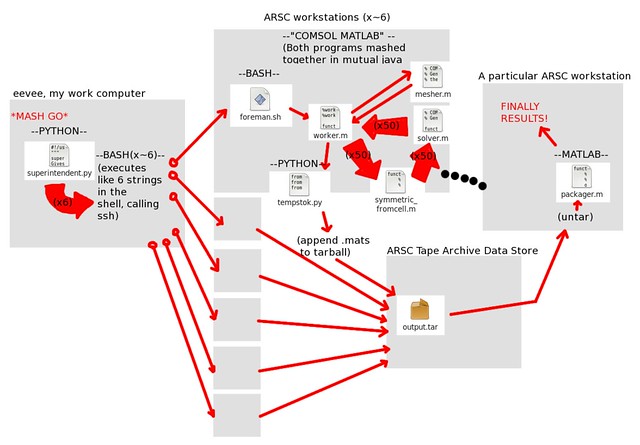

I attempted to develop a scheme that would use SSH to implement an ad-hoc mapreduce-esque scheme across a number of ARSC workstations to split the job of calulating K-values amongst about six machines.

(flickr)

Of course, looking at this picture, you might realize how crazy this idea was. Parallelism isn’t intractible, but trying to implement completely parallelism with a buggy COMSOL/MATLAB interface that doesn’t run headless very well and is hard to even start from the command line, is a clunky, time-consuming preposition. In three months of hard work, it still wasn’t working.

Of course, due to licensing constraints on the part of COMSOL were only one instance may be open at a time per person, it became a moot point.

The lesson here isn’t that ad-hoc concurrency is a bad idea. The lesson here is that one should be weary of complexity and that the importance of strong foundations shouldn’t be underestimated. People create SSH-based concurrency schemes all the time, but they’re also working with software that works just fine and as-expected, without too many kludges, on its own. Moreover, most concurrency uses pre-existing, stable frameworks. If one wanted to run MATLAB programs concurrently, for example, using The Mathworks’ parallel MATLAB framework would likely be the simplest, most robust way to do it.

If anything, what this hilights is the importance of time management with research. Given the choice between just about anything and avoiding spending more time, the correct answer is to save time:

-

Spend time to make a process faster or Just do the process as-is? The latter.

-

Spend time doing something the Right Way or Just kludge it? The kludge wins.

-

Spend time shopping for the best buy or Buy the first thing you see that’ll work? Definitely the latter. That’s what grant money’s for!

It’s a common pattern, and while it may seem to be less than ideal, it’s also realistic.

##Direct use of MATLAB’s expint() Function

Interestingly enough, MATLAB actually comes with an exponential integral function, though it’s defined differently in MATLAB than it is in this context. A failed approach involved trying to fit the data points directly against the exponential integral solution. However, the convergence properties of this approach were less than ideal.

Custom Data Logger

Speaking of time management: I also spent a good chunk of time researching the programming of my own data logger using a microcontroller. This was because I wanted to measure angle with an accelerometer and a digital compass, and working with the Campbell tools is a pain even given that all your instruments are analog in nature.

This isn’t in and of itself a bad idea. In fact, there would be many advantages to using a custom-programmed microcontroller over a Campbell data logger. However, there are other considerations:

-

I didn’t know a lick about programming microcontrollers. I know a little more now, but not enough.

-

Someone had already set up the needle probe to work with a Campbell data logger.

-

There are less technically advanced ways to measure angle, such as protractors.

The lesson here is to stay focused on one’s project, and be ever-consious of what’s doable given a certain time period. In this case, making a new apparatus would be a good project for an EE’s senior design project. However, for a Mechanical Engineering graduate student that has a number of other goals, none of which actually call for making a new measurement scheme for the needle probe, it’s not as good of an idea.

On the other hand, having followed the “spend money” rule, I now have a MSP-430 that I don’t need right now. This could lead to fun hackery down the road. Who knows?

Layered Glycerine

One of the “standards” used with the needle probe apparatus is to measure the thermal conductivity of glycerine in an insulated box. Glycerine is chosen because its conductivity is similar to water without convecting and because it automatically fills air gaps around the needle. So, I considered using glycerine as a medium to build an anisotropic material, figuring its gel-like nature would stop it from mixing.

It’s true that the gel stops mixing. However, what it doesn’t stop is buoyancy effects.

Consider, for a moment, how one would change the thermal conductivity of a fluid. Basically the only thing you can do is add something else. So, for example, I started by trying to add rubbing alcohol because rubbing alcohol has about a third of the conductivity of water. On the other hand, it’s also about 70% the density of water, and surely even a smaller percentage as dense as glycerine. So, imagine trying to pour heavy vegetable glycerine over a thinned, lightweight mixture of glycerine and rubbing alcohol. What happens, of course, is that the alcohol mixture floats on top of the unadulterated glycerine.

This shouldn’t have been a surprise, and yet it was. Interesting how that works. Instead, the experiments use straight table salt and table sugar.

Appendicising This Blog To My Thesis, and Other Literary Faux-Pas

Should’ve seen that one coming, right?

I originally intended to attach this article to my thesis as supplementary material. Of course, I was told quite frankly to “lose the blog.” Touche, sirs! I’ll admit that, at some level, I knew I was trying to pull a fast one.

Other criticisms of my thesis, as it’s written right now, are that my writing style is too informal and that I spend too much time describing the how and not the what. The first is an issue I’ve always struggled with in my writing. I find formality very difficult. Both of these, however, speak much of what different audiences expect from their reading, and about how other writing influences my own.

Science and engineering tends to report in the affirmative. Most papers and documentations focus on what did work, and what was shown as a result. Moreover, scientific writing doesn’t even really talk about the particulars of how something was done. For example, in my thesis (as-written), I showed multiple code snippets and described their function. This was uncool in the eyes of my thesis committee.

In contrast, most of the technical articles I’ve been reading lately haven’t been journal papers, but startup blogs, code tutorials and READMEs. These sorts of documents, in fact, focus on exactly what I did in my thesis—that is, the particulars of how something was done, complete with code snippets. Moreover, most hackers don’t care about such things as professional style. In fact, many would call hackers markedly unprofessional. For example, James did a presentation on dnode that had expletives in it. It’s a pretty good presentation, right? But there aren’t very many venues where “fuck yea callbacks” would be appropriate, especially outside the hacker community.

Of course, this is an extreme example. In my thesis, even speaking in the second person constitutes a “situation.” It’s being published, after all.

Anyways.

I got a busy couple of days ahead of me! I’ve pretty much written off the possibility of getting my thesis signed off by the grad school this week, but I’m hoping to get it Through The Door in the next week or two so that I can start concentrating on my class (which I haven’t attended since the last midterm) and my job (only two labs left)! If I’m extremely lucky, I’ll be able to get the grad school to accept my thesis late and give me my degree on-time. Worst-case is that I have to take a correspondence class this summer to get my degree. Most likely scenario, at this point, is that I don’t get my diploma until the end of the summer. Not a big deal, except that I’ll feel a little silly walking for graduation. Oh well, relatives.

Wish me luck! I’ll need it.